Words by Lachlan Morton

Photography by Dominique Powers

Commissioning Editor: Samuel Craven

First published on www.rapha.cc

The appeal of a reset in Tanzania was too strong.

After a wild year, I’d decided to base myself in the USA for 2023 and focus on racing there. The intention was to slow things down. But idle time is soon filled, and before long I felt busier than ever.

I remembered my time in East Africa last year had kept me sane. So I dug out my passport, booked a flight and doubled down on the packing list. The idea of a hard reset, somewhere in the night, somewhere in Tanzania, somewhere in my mind – that was the only important thing now.

After the tedious packing and charging, repacking, pumping and lubing, repacking again and second guessing, I slept like a baby. I looked forward to the solitude.

Evolution Gravel Race is an 860km adventure from the Ngorongoro Crater to the Swahili Coast. Sandy desert, high tropical plateau, corrugated roads, muddy moto and smooth single tracks, ferocious climbs and frustrating farm lanes are strung together by a series of small villages. Hives of activity in the day, these towns sleep with the sun.

The race comes in two. The first part is 460km with a mandatory 12hr stop, at a camp set up by the organizers. Then there's a 400km stretch to Pangani, by the Indian Ocean. The format lets riders experience ultra racing without the sleep deprivation competition often requires. Evolution was exactly the race I was longing for.

Beginning only four days after the Migration Gravel Race in Kenya, Evolution meant a long bus trip and border crossing. Arriving in Tanzania I met the other crazies taking this race on. Anxious first timers, curious enthusiasts, seasoned racers and eager young East African talents looking to make their name, and everything between. It took courage and commitment to toe the line at the start. It was going to take much more to reach the finish.

When the race began, I knew that other riders would gauge their efforts from mine. I didn’t want that, so I took off in the first challenging section after 60km. Sandy single track chaotically threads spiky low brush. There’s wildlife here, but navigating leaves little room to worry more than five meters beyond your front wheel.

The day grows hotter and the fun sand section gives way to forty brutal kilometres of washboard and headwind. The occasional boda boda track beside the road offers brief reprieve, but this is ugly work. A detour through a village offers a change of surface before we turn toward the hills. That might sound wonderful now, but be careful what you wish for.

I take the opportunity to stop at a small shop. The young girl attending signals for her mum at the sight of me. I buy up 4 liters of water and a liter of coke. 3000 shillings. They get a good laugh watching me drink half right then and there. There was enough curiosity to warrant a question, but they could see I was thirsty. I told them where I was heading, they rewarded me with head shakes and laughter.

Back on the road, the route becomes a mishmash of small single track and larger farming roads. I'm told the summit of Kilimanjaro is visible from these corn fields. My gaze was set on the much closer set of mountains.

An increase in foot traffic indicates the working day is over. Soon the land will be in darkness. I prepare myself: headlight on, arm warmers on, playlist change.

The initial plunge into night always brings a short sting of anxiety. It takes me a few minutes to settle. All things going well, knowing that we will be tucked up in the camp before sunrise fills me with motivation. I tackle the first major climb without walking – just. That’ll be a rude surprise for a few during the graveyard shift. There’s a small glitch in the GPX near the summit, so I call the organizer Mikel to let him know, and to work out what to do next.

Eventually I agree to ride further up the hill, adding about 7km, while they send someone to work out a reroute. It's wild how small things like this can unravel you, and I let it, but only for 5 minutes. In these moments I realize just how close to my mental limit I operate at, and the pleasure I get being there.

A technical descent leads me back to the valley, leaving just 80km to camp. But after 17 hours on the move, my Wahoo is dead. No drama. I have a spare. This desert section takes ages. It's hard to determine how deep the various sandy sections are, and there’s a god-almighty climb on the other side.

It's then that I remember I'm alone, in the Tanzanian bush, at night. I can’t help but laugh. But a massive commotion in the scrub to my right interrupts my outburst. Is that a cyclone in the bushes? Am I losing it already? It's not even midnight.

Without slowing, I turn forward to focus on the track. The bottom half of an elephant appears, running right across my path. I jam the brakes, avoiding a collision. When I see it circling back, ears up, I know I need to get the fuck out of there. I’m suddenly aware of the presence of more than ten elephants in my direct vicinity. Head down, I ride beyond my capabilities, fuelled by pure adrenaline. A magical and humbling experience. With the desert section behind me, the long climb to camp looms. The first 8km is straight, deep gravel and washboard sucking all the energy push into the pedals. I spot camps in the drainage pipes running beneath the road, dim figures lit by dwindling fires. A short descent leads to a series of switchbacks that cut straight into the side of the escarpment. I know this only from my memories of the year before. I shift to my easiest gear and do my best to spin at a respectable cadence. The climb is steep enough that it’s hard not to envy my future summit self, having ascended nearly 2000m. I do my best to enjoy the final minutes of my first push. I know that there are many riders battling far more than I am, and that thought is strangely comforting.

When I reach the camp I let the race director know of the elephant situation. It is a hive of activity, the bush kitchen in full flight and water boils for showers. I pick out the closest tent then make to get clean. A bucket of hot water behind a tarp screen has never felt so good. I scrub away the day’s efforts while bathing in the experience of a special day on the bike. After changing into some fresh clothes I tuck into some ugali, curry and fire roasted meat. The sense of calm is deep, a world away from the stampede situation earlier. After some tea, I duck into my tent at 3am. No thoughts of tomorrow, only the day that was. Inside my sleeping bag, paralyzed with fatigue, I drift off. I’m rarely happier.

When I finally rise, the sun is well up. Riders are wandering around in a daze of fatigue and satisfaction. Some eat slowly, staring blankly, lost in thought. Others fiddle with their bikes and bother the mechanic. All have stories from the previous 24hrs. I drink some coffee while doing my best to talk with as many riders as I can. The consensus was that while it had been a very difficult ride, everyone was very proud to have made it to camp. We felt we had broken the back of the race, the hardest was behind us, downhill now to the coast. I wanted to believe that, but I knew better. After a couple more meals, some recharging and repacking, it was time to hit the road again. Twelve hours to rest and replenish, without removing yourself from the ride ahead, was just right. When I set out, the following weekend’s Lifetime Grand Prix event – Crusher in the Tushar – is in the back of my mind. It's an important one. I want to cover today's distance fast, but I also don't want to dig myself into a giant hole. The route had other ideas.

A few hours in, after traversing and descending the high plateau, I find myself in one of the bigger towns on the route. Right as I reach the centre, a sudden and unmistakable feeling washes over me. My guts are seconds from evacuating. I race for a back street, strip off my jersey and fight my bibs down as I jump ass-first into a set of bushes. Close call, bad sign. After cleaning up, I roll out of town with 320km of difficult terrain ahead and hope that experience was a one off. It wasn’t. Every thirty minutes the situation repeats like clockwork – for the next ten hours. The bib straps are staying down. Luckily, there aren’t many towns out here. Just hot, dry desert. Night falls on the toughest climb of the race, reaching 1300m in only 13km. It's a beast.

Until now, I’d done my best to keep memories of last year's race out of my mind. That experience is woven into my memories of Sule, and I hadn’t been willing to go there. Now, deep in an effort that requires complete focus to push on, I can’t keep those memories from coming back. I relive the race we had only one year ago. Together, we battled up this same climb, across this same plateau. In the darkness, I relive each moment as my current reality. His death has never felt so real.

It feels terribly unfair that he isn’t here to battle again. But also I feel lucky to be experiencing his company one last time. Last year, we raced each other to the ocean. This year we race again, together in my mind.

I forget my plans, the races ahead of me, and I start to dig that hole. I dig because I want to. I dig because anyone who wins this race after Sule should dig as deep as he did.

The night becomes a blur of effort. I’m reduced to my most basic self. Deeply uncomfortable, emptying the tank is renewal. After the laughably steep final climb into the Amani forest, I let my mind wander – to the ocean. I know that when the sun comes up, it’ll be close. I know it’s risky letting your thoughts get that far ahead, but I don’t care.

Deep in the forest, my headlamp illuminates a pair of eyes. Most of the eyes I've seen so far have belonged to monkeys, high in the trees. But this pair is low, alongside the rutted mud track I'm navigating. As I approach they disappear, replaced by the figure of a large cat as it sweeps across the road in front of me. I’m close enough to see its spots. It dissolves into the forest, blending impassively in the dark as if I wasn't there, as if it had never been there.

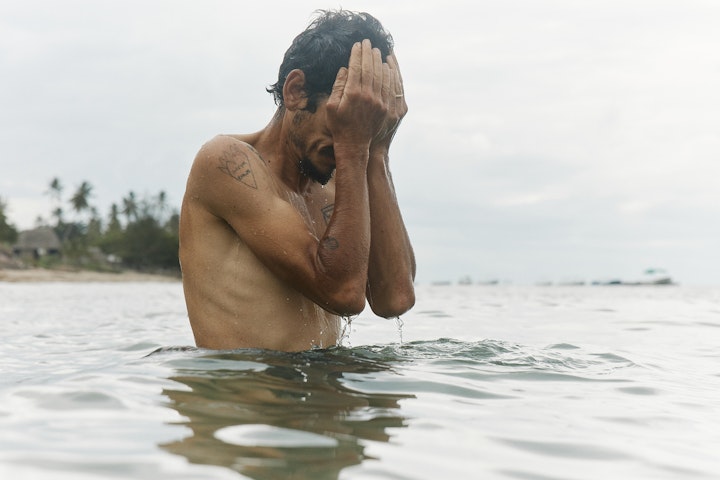

The final 80km are new this year, and they’re hard. Endless small singletrack and muddy moto trails make small hills big. I’m thirsty, and the 4am calls to prayer have me scanning every village hopefully for a store. Finally, at 6am, I find one. A small crowd of curious locals inspect my bike as I down a few liters. They look at me, wondering where I've come from. I tell them I'm heading for the sea – in this moment, it's hardly impressive. Willing my aching legs through the final kilometers, I refuse to let up. I’ve made a pact to push till the end. So I push. When I arrive, I hide brief tears in the ocean. The water holds me up – it knows there's nothing left.

I tell my stories, highs and lows. I know true understanding will be lost, only for those who have endured this same savage adventure to the ocean. And although I made this journey alone, for the most part, I feel company in the fact there were many less prepared, less experienced, less resourced individuals giving their all just to reach the finish with me. Back home I'm physically exhausted, but there's more life in me. For two days and nights, somehow Tanzania had been more comfortable than home.